Back to articles

SYSTEMS

Why Ten Thousand? - The Climb

Part 1 of 2. What happens when you pass through ten thousand feet, and why should you put it on your TBM checklist?

It's easy to know when you've crossed through ten thousand feet on a commercial flight. When the aircraft climbs through ten thousand feet AGL, the seatbelt sign comes off, the captain gets on the mic, and the flight attendants roll out the cart to start drink service. On the descent, we're told to bring our seat backs to the upright positions, the seat belt signs come back on, and the cabin crew buckles up for landing. That's what ten thousand looks like to a passenger. However, in the cockpit they are running checklists, beginning sterile cockpit procedures, and coordinating with dispatchers and ground crew at the arrival airport. Every professional crew has a ten thousand checklist, but that alone is not a good enough reason to have one.

Ten thousand should be considered a line between the 'critical' and 'non-critical' phases of flight. Below this altitude we have airspace restrictions, airspeed restrictions, and the radios become much more busy. It is below ten thousand where our workload increases dramatically and we are more likely to "get behind" the aircraft. Above, the environment around us becomes less hospitable without a properly pressurized aircraft to keep us safe, but we gain the benefit of a decreased workload and a substantial increase in aircraft performance.

Because we are moving between environments that differ so dramatically, ten thousand feet becomes a logical place to insert some checklist items to ensure that both the aircraft and the pilot are prepared for the transition.

Most checklists don't require any actions between the 'CLIMB' and 'CRUISE' portions of flight, during which a significant amount of time will have passed. Even worse, it's common to not have any checklist actions between 'DESCENT' and 'BEFORE LANDING', which is an enormous amount of time without referencing the checklist at all. Moreover, inserting a checklist at ten thousand feet promotes situational awareness by building the habit of physically reaching for the checklist and reassessing your situation an additional two times every flight.

In this article, I'm going to talk about the 10,000 FT section I've added to my own personal TBM checklists and why you should consider adding them to your checklist too. For considerations of space, I'm only going to include my TEN THOUSAND (CLIMBING) checklist in this article.

Landing Lights - OFF

What to look for:

- Landing or Pulse lights off.

- Check the lighting system.

To promote visibility and prevent mid-air collisions, the FAA recommends you keep your pulse lights (daytime) or landing lights (nighttime) on below ten thousand feet. Make sure you have the appropriate ones activated for your flight.

Oxygen System - ON

What to look for:

- Oxygen switch is in the "ON" position.

- Oxygen quantity is sufficient for the flight and doesn't reveal any leaks.

This is one of the first items I take care of while I'm still on the ground, but it's prudent to check the Oxygen Pressure and Oxygen Switch on the overhead panel at ten thousand feet. Although the required use of supplemental oxygen above 12,500 feet (MSL) does not apply to our pressurized TBMs, the requirement very clearly addresses our inability to get sufficient oxygen at those altitudes should we have a problem with our pressurization system. Even with pressurization, we are still required by the FAA to have 10 minutes of supplemental oxygen for flights above FL250 (14 CFR 91.211(b)(1)(i)). This is an important check, but one that is quick and easy. Make sure the switch is on, and the tank has enough air.

Pressurization - CHECKED

What to look for:

- A positive differential pressure.

- A positive or zero rate of cabin climb.

- An expected cabin altitude.

You shouldn't have to worry about emergency oxygen too much as long as your pressurization system is managing the cabin altitude correctly. But before we get into a hostile environment, we need to check and correctly interpret the pressurization indicator.

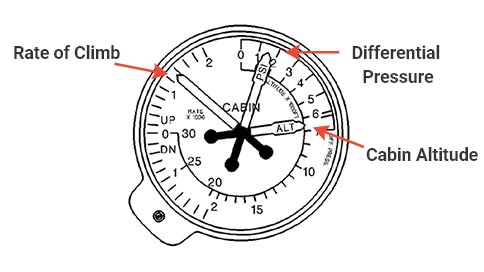

Cabin Pressure Control System

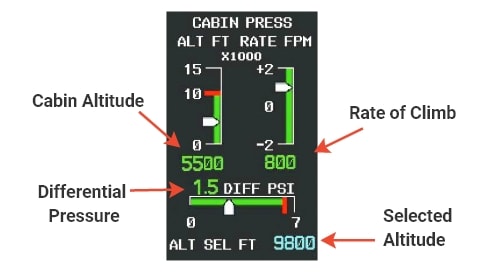

Garmin GDU 1500 MFD

We should see a rate of cabin climb around 500 feet/min on systems that automatically set the rate, while older systems allow you to set it manually. Take note of your current cabin altitude compared to your desired cabin altitude. If the cabin hasn't reached the desired altitude, check for a positive rate of climb to make sure that the cabin is actively climbing. If you've reached your desired cabin altitude, ensure that the rate of climb has returned to zero. Monitor differential pressure to make sure it doesn't exceed 6.2 psi.

Fuel Pressure/Balance - CHECKED

What to look for:

- Fuel imbalance that exceeds limitations.

- Expected GPH indication.

- Expected fuel burn.

It's likely that we haven't looked at the fuel since takeoff, especially if the departure was busy. So ten thousand feet is a good time to check our fuel and manually switch to the fullest tank if there is an imbalance. We should also look at our total fuel load and consider, "Given our departure, have we burned an appropriate amount of fuel?". Take a look at your total fuel burn and the current GPH (Gallons per hour). Do the numbers make sense? Do we have a leak? Are the fuel caps on? Consider using this checklist item to not just balance the fuel but as the last opportunity to evaluate the operation of the fuel system before you create too much distance between your aircraft and the departure airport.

CAS Messages - CHECKED

What to look for:

- Missed Cautions

- Separator

If you canceled a warning during the departure that could be managed at a later time, now is the time to check. Looking at the CAS panel will also remind you of the status of the inertial separator, which is very important for the next item.

Climb Power - SET

What to look for:

- Consider Separator/ITT

- Torque set at Max Climb

If I haven't disengaged the separator by ten thousand feet, I'm looking for an opportunity to do so.

Remember, the performance charts in the POH assume that the separator is disengaged when providing power settings for climb. When the separator is engaged, the climb power settings are no longer accurate, and it's necessary to provide a power setting that maintains ITT within limitations. Moreover, if we keep the separator engaged above ten thousand feet, we don't receive the benefit of the digital assistance provided by our avionics.

Falling below max torque.

Most TBM cockpits have a 'max-climb triangle' that appears above ten thousand feet on the TRQ% indicator. Pushing the power lever up to meet the max-climb triangle assures that the aircraft is getting the maximum available power for the given conditions.

When climbing above ten thousand, be sure to keep pushing the torque up to the "max-climb" setting indicated on the torque meter or as documented in your performance charts. The power requires constant attention. It is never 'set and forget'.

Remember, there is an awful lot of time between your CLIMB checklist and your CRUISE checklist. Consider adding a TEN THOUSAND section to your personal checklist to check on your aircraft and yourself. In my next article, I'll talk about the Ten Thousand (Descending) checklist that I use.

Fly smart, fly safe.

Adam Kudzin is a TBM Instructor with over 4300 hours in the Daher TBM Series of aircraft. He produces videos, writes articles and creates training materials for the TBM Owner/Pilot community on his website, Flythetbm.com.

This article solely reflects the views of the author and is not intended to replace the information in the aircraft POH.